Unravelling the Reasons Behind the 4.3 Million Home Deficit

According to the non-partisan Think Tank Centre for Cities, inefficient and outdated planning laws are at the heart of the sector falling behind its housebuilding targets, with a 4.3 million housing deficit being a product of this. Housing Industry Leaders highlights the main findings from the report.

With over 4 million houses missing from the housing market, the UK is dropping behind its European counterparts as the housing crisis deepens. Addressing this backlog is crucial to solving the current housing crisis, but how we do this is still heavily debated.

To help solve this challenge, the sector needs to increase the size of the UK’s housing stock by 15 per cent. However, this requires policymakers to understand and resolve the root cause of such a significant problem.

‘The Housebuilding Crisis’ report by the Centre for Cities highlights how laws have seen the UK housebuilding rates drop significantly below European averages over the last 70 years, creating a backlog of at least 4.3 million homes that could have been built, dating back to the 1950s.

Britain Has Built Fewer Homes Compared To Other European Countries

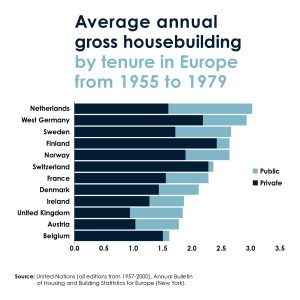

The report usesly available data on housing, thatected after the Second World War by the United Nations. This data and other sources have been used to compare British housebuilding and the outcomes to that in Ireland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, (West) Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland from 1955 to 2015.

Compared to most other European countries from 1955-1979, Britain built far fewer homes even after adjusting for population growth, initial population, demolitions, and quality.

The report explains that it is essential to address the problems with the discretionary planning system to solve the housing crisis. To do this, the Centre for Cities highlights that the discretionary planning system must be replaced with a new rules-based flexible zoning system. Increasing the certainty of the planning process and the supply of land for development is essential for any significant increase in housebuilding, whether by the private or public sectors.

Private sector housebuilding must increase to help tackle the housing crisis. More council and social housing can be part of the solution, but given the scale of the backlog, significantly increasing the amount of private housebuilding will be crucial.

Why Has Under Delivery Of Housing Become The Norm Since WWII?

The scale of underbuilding in Britain since the Second World War means that the UK should have more homes than it currently does today. In the report, it is expressed that it is possible to produce reasonable estimates of how many homes the UK would have added had it seen its housing stock grow at a similar rate to other European countries every year from 1955 to 2015.

Had the UK built houses at the rate of the average Western European country from these years, then it would have added a further 4.3 million homes than it did. This would have resulted in 15 per cent more homes than the 28.3 million dwellings that did exist in 2015.

As the UK increased the size of its housing stock by 12.2 million homes from 1955 to 2015, these extra homes would have required new additions to be 35 per cent higher across the entire period.

It is said in the report that if the UK had added homes at a similar rate to Finland, it would have added an extra 8.3 million homes from 1955 to 2015. This would have been a 30 per cent increase in the 2015 dwelling stock.

If the UK had adopted Denmark’s relatively subdued approach to housebuilding, it would still have an additional 2.5 million more homes than it does today, a nine per cent increase in the total dwelling stock in 2015.

Policymakers Need To Recognise The Scale Of The Housing Crisis

Going forward, housebuilding in the UK needs to be high enough to meet both normal annual demand and make progress in clearing the backlog of 4.3 million unbuilt homes.

At present, England has a housebuilding target of 300,000 a year, which implies a rate of 1.3 per cent annually. If Europe continues building at its current rate of 0.9 per cent, England building 300,000 homes a year will take 65 years to close the housing backlog.

However, it is difficult to imagine a future where the UK meets its housebuilding target as at the end of last year, the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Michael Gove, expressed that the target will be a “starting point” and become “advisory”, and said that he recognises: “There is no truly objective way of calculating how many new homes are needed in an area” but that the “plan-making process for housing has to start with a number.”

Ending the current housing crisis in the next twenty-five years would require England to add 442,000 homes every year, double the current housebuilding rate of 220,000 a year. While to solve it in ten years, 654,000 new homes a year in England would be required.

To see change, the new home target for England must be increased, the scale of the housing crisis challenge must be recognised by policymakers, and the current Town and Country 1947 planning system of England (and the devolved nations) must be replaced.

A new flexible zoning system would increase housebuilding and end the housing shortage. The report explains that this would see a flexible zoning code designed by national and devolved governments for local governments to use in local plans.

Streamlining Plans Could Increase Housing Delivery: Here Is How

When it comes to this plan, rules must be in place to state the planning proposals that comply and building regulations must be granted planning permission. The zoning of land within walkable distances around train stations in the green belt for suburban living and with protected green space would provide 1.8 to 2.1 million homes.

In addition, Local Plans and Local Transport Plans, which are currently different documents, should be merged into the same document. This means that planning for development would require planning for infrastructure and vice versa. However, with zoning in the planning system, the public will find having a say on new developments difficult. The move to a zonal system reduces the possibility for public input and democratic accountability by half.

Currently, England has a two-stage process where local councillors and the public can comment on both the formation of local plans and individual planning applications. It could mean that it may take many years in advance for particular schemes to be given the go-ahead.

Many people are against the idea of zoning because zoning can have an effect on the development of housing. Not only can it discourage some development in some locations, but to a certain extent, zoning limits the development potential of previously existing land uses and structures that do not conform with the zoning’s standards.

In addition, zoning requires that all involved property owners relinquish some of their individual property freedoms for the common good and can increase the cost of building new structures. Zoning can work against historic mixed-use neighbourhoods in older communities, and properly enforcing a zoning ordinance involves a long-term commitment to a certain level of community spending.

Another way in which things can become more streamlined is through the addition of a better organised and frontloaded public consultation in the creation of the local plan rather than individual proposals.

The effect of these reforms would mean that instead of development is prohibited on all land unless a site is granted a permit by a local authority, the development would be allowed on more urban land and undeveloped land near cities unless it was specifically prohibited.

Reforms in policy areas, such as local government reorganisation and fiscal devolution, would help enable improvements to the planning system. Centre for Cities expressed that this should be on the table for any government that is serious about achieving the best possible housing and economic outcomes.